Beacon Hill hosts teach-in event at Decatur Square

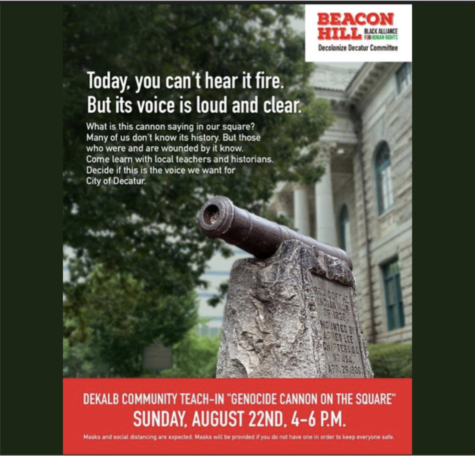

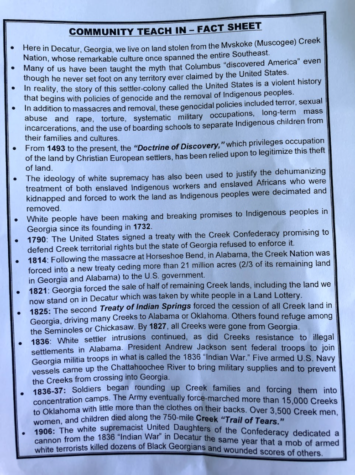

On Aug. 22, the Beacon Hill Black Alliance for Human Rights hosted a community teach-in at the Decatur Square. Beacon Hill invited several teachers from multiple districts in Metro-Atlanta to speak out for the removal of a cannon commemorating the 1836 “Indian War”.

The teach-in lasted from 4 to 6 p.m. and spanned several topics, including the original history of Muscogee people in the region leading up to their expulsion in 1836. The presentation was concluded with a call to sign a petition advocating for the removal of the cannon. The petition has over 1800 signatures as of Sep. 2.

Decatur High School (DHS) social studies teacher Jennifer Gonzalez was one of the speakers at the event. According to Gonzalez, the concept of Beacon Hill’s teach-in idea is that “everyone would know the history of that cannon, the details surrounding why it was put there, and what it represented in addition to the people that it was talking about… Once you know what it’s really about, it’s way easier to make an informed decision [about its removal].”

![]()

In addition, several speakers highlighted the problems with the origin of the cannon. “I think [DHS teacher Javier] Fernandez did a great job at explaining that the Muscogee people, who were named the Creek by the colonizers that came in, were killed in what was referred to on the cannon as the ‘Indian Wars’, in this kind of neutral term. War implies equality, which it wasn’t, and so it falsely celebrates a massacre of people,” Gonzalez said.

The cannon was erected in 1906 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the white supremacist group that also placed the Confederate obelisk that was taken down in June 2020. 1906 was also the year of the “Atlanta Race Riots”, when mobs massacred dozens of black people around Atlanta.

“The Atlanta race massacre happened in response to a growing black community, a growing successful black community in Atlanta,” Gonzalez said.

“To put these two different objects in the middle of the square in front of what would have been City Hall: one being a monument celebrating the Confederacy and the virtues therein, and one being an antiquity of war, and all the violence that that implies, and pointing that at potentially a line of people who were trying to break down barriers in terms of accessing their very constitutional right to vote, I think that’s important,” Gonzalez said.

Because of the time period when the cannon was placed, Anthony Downer believes that now is the right moment to remove it. Downer is a history teacher at Frederick Douglass High School in Gwinnett County.

“What we’re seeing, like you saw 100, 110 years ago is this displacement of black and brown bodies from their communities and their native populations. We’re seeing economic and political attacks on black and brown individuals, so this is a time for us to be courageous and to double down on how we teach authentic history,” Downer said.

When it comes to the history curriculum in schools, Downer believes there are additional challenges. While he successfully added an ethnic studies course to his school, there has been nationwide backlash against discussing race in classroom settings.

“Teachers must understand how education is politicized, how the curriculum has been used as a tool of the power structure,” Downer said.

In May 2021, Georgia Governor Brian Kemp passed a decree saying that Critical Race Theory (CRT) should not be taught in Georgia schools. No law has been passed yet, but Gonzalez fears that a more forceful ruling would interfere with Decatur’s ability to “reconcile ourselves by teaching truth”.

According to San Diego law professor Roy L. Brooks, CRT is a “collection of critical stance against the existing legal order from a race-based point of view.”

Gonzalez thinks that CRT “has become this lightning rod and has been defined and mis-defined several times,” but still asserted that an inclusion race is crucial in the teaching of history.

“To ignore that race is a part of history is just not teaching what is actually happening. So to ignore, for example, the fact that this thing in our square is about the massacre of Native Americans is problematic,” Gonzalez said.

There have been current examples of the erasure of history in the high school curriculum, Gonzalez said. In 2020, the U.S. History textbooks universally changed the name of plantations to “commercial farms”. She explained that this change was problematic because if students haven’t been taught in class about “commercial farms”, they will be lost when that term appears on the final exam, and will likely perform worse.

In addition to erecting monuments and statues honoring Confederate soldiers, the United Daughters of the Confederacy reached into the curriculum of primary and secondary schools, spreading the “lost cause” mythology that Confederates were fighting for their own rights, not for the enslavement of African Americans.

Despite the limited power of teachers, Downer believes they are crucial in the upbringing of an informed youth.

“Teachers need to be on the front lines, and it needs to happen K through 12,” he said. “Students need to have a curriculum that embeds and incorporates criticality, intellectualism, and joy. And that, again, is paramount for our marginalized learners, our students with disabilities, English language learners, and our low-income learners.”

Downer was inspired to speak at the event because of his role as well as his relationship with Beacon Hill.

“They’ve helped us build a coalition for equity in Gwinnett County, so I wanted to pay that back and recognize that partnership by coming out,” Downer said. “When we talk about coalition building, we need all school districts to really push forward that multicultural representative history in the curriculum that we’re fighting for.”

As a member of Beacon Hill, Gonzalez described the importance of community education when the school curriculum is limited.

“Beacon Hill has always been about teaching truth whether or not it’s in school. So, that action was on a Sunday, was not in a school building, and that’s an example of the community teaching curriculum, which I think is also important. Don’t just leave it to the school to teach what people need to know,” Gonzalez said.

At the end of the event, Gonzalez and fellow teacher Jennifer Young drew a blue chalk line on the sidewalk with several breaks representing the erasure of history. Community members were then asked to write something that they took away from the teach-in, which they would remember even after the chalk faded. The activity was inspired by Gonzalez’s own experiences in Decatur.

“When my daughter was here at Decatur High School, she was in the politics club, and she tried to debate with her friends about the Confederate monument and she said, ‘Mom, there’s nothing, I googled, I can’t find any research to support the idea that the Confederate monument is anything except awesome’, and I was really troubled by that erasure,” Gonzalez said. “That’s the demonstration that we did. It was that the records have been erased. And I need for students today to be able to have access to information so that they can see that there’s more than one side, and that they can see complete and true history as complicated as that is.”

Gonzalez is optimistic that the cannon will finally be removed from the square and be relocated to a museum or archive.

“The City Council is talking about removing it, and I think that the community just needs to give the push,” she said.

Downer is also hopeful about the future of community events like the teach-in.

“I hope that we’re taking advantage of getting back in-person, safely, by building relationships and alliances that withstand the test of time,” Downer said, “but also that we are serious about our anti-racism, about what we have to do in our daily lives: for men to break down the patriarchy, for heterosexual folks to break down the heterosexual framework we have, for white people to break down anti-blackness, and for all of us to think about ways that we can involve and educate ourselves.”

Adrien Tirouvanziam (Class of 2022) enjoys sports, music and academics all up to a certain extent. If you look down enough, you can find him playing...