Life Inside the “Not-So Padded Walls”

Student learns to cope with depression

November 29, 2017

Mary Lambert’s* glass was full to the brim with her newly discovered concoction, sweet tea mixed with raspberry juice. She devoured her chicken nuggets dipped in honey mustard, sitting next to her roommate as they got to know each other. The growling stomachs, rush to get food and loud conversations were the only commonalities between her life at Ridgeview Institute, an intensive care unit in Smyrna, GA, and her life at Decatur.

The summer before her freshman year, Lambert spent most of her time away from school with friends and traveling. But her worry-free life in the classically humid Georgia summer was turned upside-down. She had developed depression, a mental illness on which she would become an expert.

“I felt like I wasn’t welcome in my family and like they weren’t proud of me,” Lambert said. It was these feelings of not belonging that sparked her depression.

After spending many hours in therapy sessions, Lambert’s doctor decided Ridgeview needed to be the next step in helping her depression and occasional suicidal thoughts. Lambert admitted herself shortly after.

At first, the idea of a new life in a hospital roughly 40 minutes away seemed like an easy escape from her troubles at home. But after entering the front doors, her entire opinion flipped.

“I thought, ‘Holy cow, this is real’,” Lambert said.

As Lambert walked through the one-story hotel-esque lobby, reality finally sunk in. She would be spending a week of her life in a place with which she was completely unfamiliar. Lambert felt like an outsider.

“I thought, ‘I’m not going to be anything like these people; I’m normal and I don’t need to be here,’” Lambert said.

She imagined her room protected by padded walls and fellow patients wearing bland uniforms.

Lambert found herself having to adjust to the new hospital rules thrown at her. Common objects were forbidden, such as colored pencils, crayons, markers and sharpies. These tools had become Lambert’s favorite form of expression back home.

“That really affected me because I used to draw every night before I went to bed,” Lambert said.

Nights were long in the hospital. Patients’ sleep was interrupted every 30 minutes by a staff member gripping a flashlight. The counselor’s goal was to ensure that every teen was safe from harm, as many were suicidal.

Days in the hospital started early. After being woken up, patients were sent to breakfast, Lambert said. Then, their blood pressure was taken and they were given their medications. Their day could officially start after they “did their hygiene”, as the staff would call it. They were sent to brush their teeth and get dressed.

Over Lambert’s week long stay at Ridgeview, she became a part of many of the support groups they offered.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy, also known as “DBT”, was one of the more common groups provided. According to Dr. Marsha Linehan and her studies, DBT has a reputation of being an extremely successful treatment for countless disorders.

It taught patients “skills that you can use to help with what you’re going through,” Lambert said. The staff introduced the patients to a way of getting rid of anger- sticking their heads in a bucket of ice. To reduce anxiety, one might start drawing, while another that is feeling depressed could go on a run. The skills learned are not meant to solve the issue entirely, but instead present tactics they can use in the moment.

For Lambert, most support groups felt like a waste of time. She found little to no help in the counselors’ advice.

“They would say, ‘Don’t think that’,” Lambert said.

She didn’t feel any real benefit until she participated in two groups she felt were immensely powerful.

“They were a little smaller than the rest of the groups, and I felt like the teacher knew what they were talking about,” Lambert said.

The smaller group allowed Lambert to have more one-on-one time with the counselor, and receive more relevant help.

The patients in these groups also contributed to Lambert’s experience. She noticed the differences in attitude between the patients in Ridgeview for their first time, and the ones who had been there before.

“Most people there for their second time had a more positive attitude,” Lambert said.

Although Lambert loved being a part of groups with less patients, she had no trouble making friends with her peers.

“You could relate to each other, no matter what your issues were,” Lambert said. Because of this, she became friends with her “hilarious and somewhat rebellious” roommate over that short period of time.

Despite the connection she had made with these people in the hospital, Lambert was more than relieved when it came time for her to leave.

“I thought, ‘Thank God I’m out’,” Lambert said. She had missed being outdoors, a privilege that she now realized had taken for granted.

Along with all the excitement about returning home, Lambert also worried about the drastic differences between the two lives.

“[In Ridgeview], you knew you had protection all around you and actual support,” Lambert said. “When you [went] home you may have had some support but not 24/7, [like in the hospital].”

Although Lambert could finally draw at night again, the hospital asked for certain objects, such as knives and locks on her doors, to be removed from her house her first few weeks back. With more rules controlling her life, Lambert felt a shift in her family dynamic. However, the change that she felt didn’t last too long.

“It eventually got back to normal,” Lambert said.

Every day in the hospital, Lambert discovered a new way to either miss home, or dread leaving through the big glass doors. But when she was finally allowed go back to her family, she recognized a change in herself before and after Ridgeview.

“Before I went in there, [I felt] useless in this world,” Lambert said. She had been looking and officially failed herself in finding a reason to live. But after Ridgeview, her vision had become clearer.

“I thought, ‘My life doesn’t really suck that much. I’m just putting my attitude towards the negative things in life,’” Lambert said.

Lambert supports the idea of seeing a therapist or living at Ridgeview.

“If you’re depressed or suicidal I would say definitely go see a therapist, but also admit yourself before anything gets worse,” Lambert said.

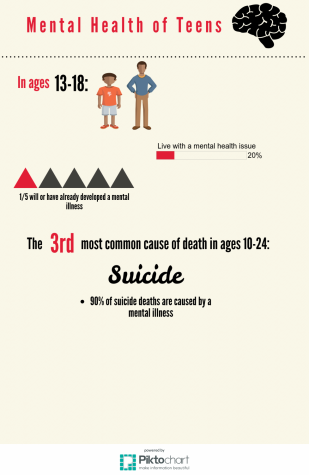

Lambert truly believes that teenage mental health is a serious issue that many look past.

“It should be made more aware to people,” Lambert said.

But people like Dianne Thompson, the Student Success Coordinator at Decatur, are working to do just that.

Thompson has been in the counseling and education workforce for 23 years. She has worked in all levels of education, as well as in other districts. However, her job this year is not like anything she’s done before.

“My position is new to the school district, and so my title is “Student Success Coordinator”, and while I have some district responsibilities, one of my main things this year is to take some of the information we’ve collected and other data sources to identify areas where we feel like we can support students,” Thompson said.

Thompson hopes the creation of a support center at Decatur would be one of these ways to further assist students in need of help.

“[The support center]’s going to have an academic component where there will be tutoring and a career component where you can do more exploration: looking at colleges and scholarships,” Thompson said. “Then there’s also going to be this social or emotional [component]- but social emotional is more than just mental health. It is also going to be helping you guys to transition into your next step.”

That next step refers to the areas most often taken care of at home that the school feels they should address- anything from etiquette lessons to doing laundry. Thompson isn’t the only staff member searching for effective ways to improve the school in these areas.

“There really is a team that is working,” Thompson said. “We kind of want to be like your safety net.”

Because of Thompson’s years of experience, she is able to construct a reasonable idea for why mental health heavily affects teens.

“I honestly think that a large part of it is that your world is a lot faster,” Thompson said.

The ability to deal with sadness has become a lot harder as new pressures, such as technology, can keep the teen from fully detaching themselves from a problem, Thompson said.

Thompson hopes to address this problem.

“We’ve been talking with the counselors about offering resiliency groups,” she said.

The support groups would also take into account that many student mental health issues have most likely developed over time.

“I think that if we did more prevention, I think that we could mitigate some of the extreme situations,” Thompson said.

Overall, Thompson has found teen mental health carries a stigma for many affected.

“I think one of the things I hope we can do as a group is change the discussion around mental health,” Thompson said. She believes this problem can be fixed by encouraging anyone struggling that they are not the only ones, and to admit they need help.

But what Thompson hopes for the future is an idea that Lambert was learning the whole time at Ridgeview Institute.

“What I hope will come out from the work at the center is that we’ll all put more tools in our toolkit and be able to address whatever comes along,” Thompson said.

*Source requested anonymity